Could Xindi be the Most Expensive Botnet yet?

by Rebecca Muir on 18th Nov 2015 in News

Today (18 November), Pixalate has issued a cybersecurity threat advisory about the discovery of Xindi botnet, which will, if not stopped, cost advertisers an estimated USD$3bn by the end of 2016.

Xindi is a Windows-based botnet specifically designed to exploit a critical vulnerability in the internet advertising protocol (Open RTB v2.3) that has infected 6-8 million machines from reputable, high-value networks, such as Wells Fargo & Company, Citigroup, General Motors, Marriott International, and Columbia University, and turned them into botnets to launch attacks against advertising exchanges.

ExchangeWire spoke exclusively to Jalal Nasir, CEO, Pixalate and Khalid Razzaq, VP of product management, Pixalate (pictured below) about the discovery of Xindi and how the industry can continue to fight back.

ExchangeWire: What makes Xindi different to previous botnets?

Pixalate: In our work to determine what the types of fraud are, we saw a new type of fraud. We observed a very interesting pattern and found a specific botnet with two signatures; firstly, it exploits vulnerability in RTB protocol; secondly, it seeks computer networks within enterprises and educational institutes. It has been able to exploit those networks and a protocol vulnerability to game the system.

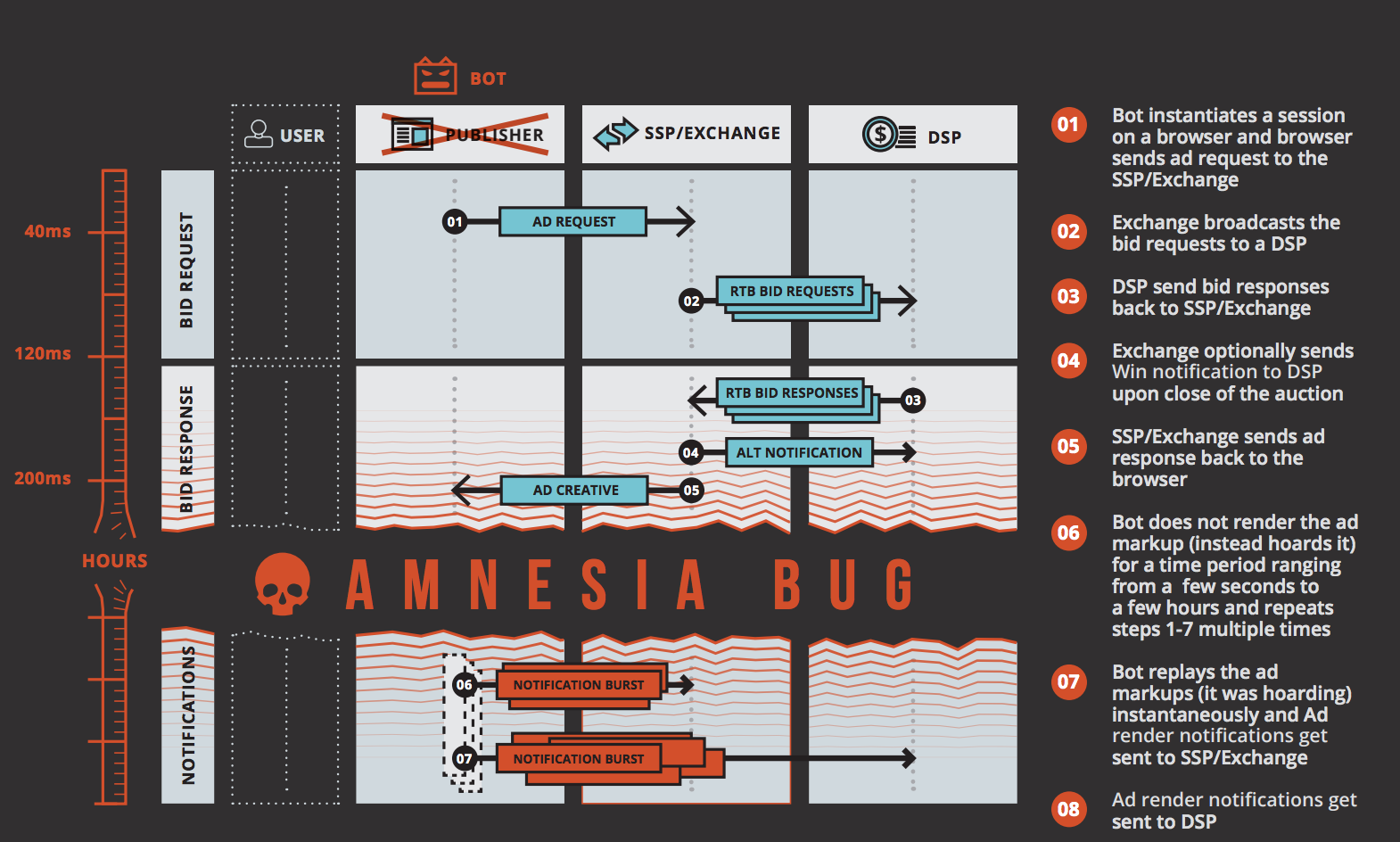

Xindi works by holding onto bid opportunities. When a bidder bids on an opportunity, the bidder expects to receive verification that the ad has rendered. When Xindi is holding the impression, this verification doesn’t get to the bidder, so it continues to bid for the impression, offering multiple bids at incremental prices. Eventually, the bidder will receive a notification that hundreds of the same impressions have been bought as a result of this repeated bidding.

Source: Pixalate Botnet report

There are certain things that work best for fraud, for example, if you’re not able to detect the activity, or, if you cannot block the activity – that’s ideal for fraud. Large enterprises and educational institutes, such as those targeted by Xindi, have thousands of computers, linked to a proxy IP, with a reputable label. This makes it harder to block fraud as you would have to block the whole proxy IP, which equates to hundreds of machines and, therefore, thousands of impression opportunities.

Furthermore, enterprise and educational institutes provide exchanges with the best users, CPMs are 5-6x higher for these users, compared to ‘normal’ household users. Finally, many of these IP addresses are found under reputable industries so exchanges do not block them.

RTB protocol and programmatic advertising has been built on trust. For example, if a bidder receives a bid request, it trusts that the information it receives with that request is accurate. Fraud exploits that trust. Today’s programmatic advertising is run on systems that were built 5+ years ago – perhaps they are already out of date?

The Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG) was formed to crack down on fraud by providing transparency into where inventory has come from through the use of unique identifiers set at the publisher level. If an impression comes through without a label then it is an immediate red flag that it has come from outside TAG.

Earlier this month (3 November), at ATS New York, four stalwarts of the anti-fraud industry discussed the recent rise in popularity of botnets; the value trade that exists between media buyers and botnets; and what the future looks like for anti-fraud and verification companies. The panelists were: Robert Blackburn, VP Sales, Equinix; Michael Tiffany, CEO, White Ops; Andrew Casale, president & CEO, Index Exchange and David Sendroff, founder & CEO, Forensiq.

Fraud is not new – it’s just got more popular

Programmatic ad trading has caused digital media spend to increase, without the need for human oversight. This has made online advertising more attractive to fraudsters.

David Sendroff, founder & CEO, Forensiq, said: “Fraud has been around since the beginning of advertising”. Andrew Casale, president and CEO, Index Exchange built on Sendroff’s point, he said: “Fraud always been there, programmatic made it popular.”

Michael Tiffany, CEO, White Ops spoke of “an explosion of sophistication” in botnets. In the past, it was possible to monetise an astonishingly simple bot net, but today’s bot nets can fake identities and they can copy cookies and game targeting systems. This is a fairly recent phenomenon.

The value trade

Fraudsters are skilled in understanding the value trade that exists between media buyers and media sellers. When supply lags behind demand, as it does in video advertising, CPMs increase. The revenue from these impressions should go to the publishers who are meeting the demand of advertisers, however, because there is significant revenue at stake, fraudsters exploit the opportunity and find a way to game the system.

In video advertising, brands are trading on attention and paying for viewability. Therefore, botnets have developed to game viewability meaning that brands are not getting the attention they’re paying for. The upgrade cycle is nearly complete; viewability in the bot community is almost greater than viewability in the human population.

The elimination of fraud is an opportunity for the premium sell-side. A transition to only buying human impressions will decrease the liquidity of the market. Botnets have created unrealistic expectations of reach because they can alter their demographic profile and allow marketers to buy, for example, 12 million Hispanic females, in market for an automobile, in Idaho, this weekend. Bad networks can say no to the money offered for such audiences, or they can say yes and find cookies that match that audience, i.e. bots.

In order for fraud to decline, the cost of executing needs to surpass the revenue gained. If the cost of operations can be increased, supply of botnets will fall. Then fraudsters will return to low-cost, easy to detect forms of fraud in order to make money.

There’s no question that we’re in the early days of botnet cyber crime, security of modern day devices is too weak, boarders are too porous, assembling giant botnets is too attractive. Computers today are no harder to break into than they were 20 years ago, we’re looking at a multi-year fight to improve security, so we have to focus on ways to make the crime less attractive.

The internet has revolutionised the black market. Online marketplaces mean that buyers have no idea who they are buying from, but they see 6,000 people have given them a rating of 4.5 stars out of five, creating a veil of perceived trust.

It’s not just consumer marketplaces that operate in this way. The explosion of cybercrime has happened because for the first time, different parties can transact and interact. It used to be individuals who committed cybercrime, now there are people who specialise in the production, package and online sale of crimeware and they well to people who know how to avoid law enforcement.

Follow ExchangeWire